|

Bhutan Development |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

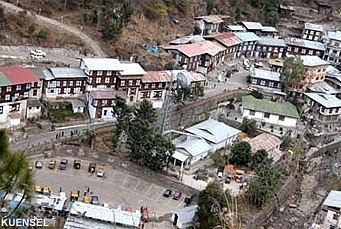

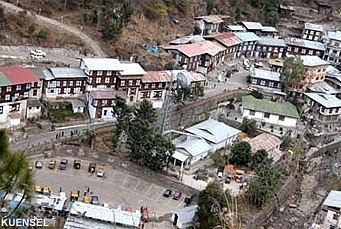

Trashigang:

Impact of the urban drift

|

|

|

Bridge

to benefit 250 households

|

|

|

Mention

rural urban migration and images of village bumpkins leaving the countryside

in droves for a life in the big city comes to mind.

That

has not quite been the case in Bhutan. If people left the villages it was

usually after completing education and landing a job in place other than

their own village. |

|

It

probably started in late 60s when the government, extremely short of human

resources, employed anyone who had some years of schooling. These people

started a new life in a new place.

Villagers

that left the countryside for a life in the city were those taken by city

relatives as domestic help or to look after orchards beyond the municipal

boundaries or for schooling. Some had left to live with their children

working for the government or in the private sector.

This

gradual influx, while filling urban centres with people from every corner

of the country, has resulted in empty houses in the countryside.

In

the urban centres it has meant pressure on basic amenities like housing

and water supply. In the villages it has affected rural development activities.

Take

for example Bidung, a village in Trashigang with about 440 households.

Of this number more than 80 houses have no one living in it and some have

been vacant for over 20 years, say gewog clerk, Kinga Wangdi.

"It

is a problem when there is a need for labour contribution as there should

be a representative from every household. Only those villagers who are

in the village keep working," he said.

He

said that a resolution was drawn up by the Dzongkhag Yargay Tshogdu two

years ago that the households who did not contribute labour should pay

Nu. 1,000 to make up for the unwanted absence. "But that remained just

on paper and was never implemented," he said.

It

also created inconvenience when collecting various taxes and insurance

premium from public.

|

Trashigang Town

Kinga

Wangdi said that some of those who had left visited the village once in

three to four years and some had not shown their face for years. "Some

pay taxes through their relatives but many do not pay on time," he said,

adding that it added to the problem because unlike other taxes, revenue

for house and life insurance had to be deposited annually to the government.

A 24 percent fine was levied annually if they failed to pay taxes within

the given deadline. |

|

Karsang,

a village tshogpa, said that some of the vacant houses and the land were

almost covered by trees and bushes. This had led to the increase in the

number of wild animals encroaching cultivated areas.

"Although

some have leased out their land to those in the village, most of it, especially

steep unfavourable ones remain fallow," he said, adding that a few of the

houses had been occupied by extension officers. Some of the houses had

also fallen apart without proper renovation.

Meanwhile,

families back in the village had, on several occasions, raised the issue

that it was not fair that they keep contributing labour and taxes while

those who left the village escaped both.

"Even

we have our children in town but we feel it is our responsibility to take

care of our phazhing (ancestral land)," said farmer Tshering Phuntsho.

"We associate our identity with our village but what is the use if you

are not going to take care of your own village," he said. "If a person

is meant to succeed, he can do it anywhere."

Tshogpa

Karsang said that the village would be a better place if people came back

and took care of their possessions. "The government should come up with

strategies to bring them back," he said. "Leaving ones roots is not a good

example for the future generation."

| Contributed

by Kesang Dema, KUENSEL, Bhutan's National Newspaper, 2007 |

|

top

| more information on Bhutan |

|

|