|

Bhutan's

Education |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

Samtse:

Schoolwise in Sengdhen

|

|

Come

2007 and Bhutan will cross a significant milestone in its evolution as

a nation.

The

installation of Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck as Bhutan's first hereditary

monarch of the Wangchuck dynasty following the unification of the country

was the beginning of a brave new world for this jewel of the Himalayas.

|

The

covenant sealed on December 17, 1907, in Punakha's Palace of Bliss was, among other things, the affirmation of the most essential factor in

the creation of a nation-state - the sense of solidarity.

Since

then, diverse enlightened initiatives and instruments envisioned and pursued

from the kingdom's serthri (Golden Throne) have refined and reinforced

a consciousness of nation and national identity. |

|

The

early acknowledgement and provision of education as a powerful instrument

in the creation and advancement of the idea of nation and nationhood has

produced rich dividends. A call to engage the marvels of the Bhutanese

mind, to affirm and celebrate the inner and the essential, to brave and

to beckon the possible and the positive of the outer, and to commit the

genius and creativity of the Bhutanese people has been a decision at once

enlightened, at once courageous.

|

|

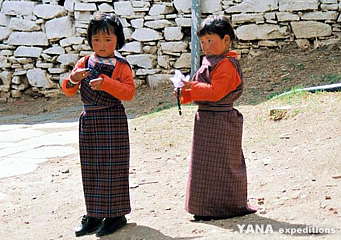

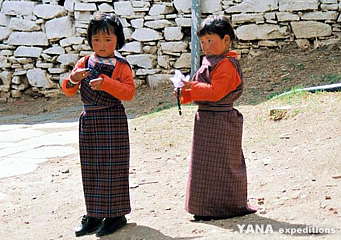

School

near Thimphu |

The

national flag adorns the Bhutanese skies, the national anthem beckons the

pupils in their tens of thousands, six days a week, nine months in a year

across the length and breadth of our country calling us unto ourselves.

The courses and curricula, the songs and the dances, the prayers and the

observances, ceremonies and celebrations all serve to bring us home to

ourselves and to our priorities. They bring us together - in our actions,

in our thoughts, in our imaginations.

| Sengdhen

Community Primary School in Samtse's Dorokha Dungkhag |

|

Sengdhen

Community Primary School in Samtse's Dorokha Dungkhag is a case in point.

Designed to bring the light of learning to one of the most disadvantaged

communities in one of the remotest corners of the country, this school

is the Lhop's window to the rest of Bhutan and to the world. Followers

of a unique way of life with a distinct language, beliefs and rituals,

customs and costumes, the Lhops or Doyas inhabit the seven villages

of Jigme, Singye, Wangchuck, Sanglung, Satakha, Sengdhen and Lapchegaon

that consist of some 120 households with about 1,000 members in all.

Deeply

inward-looking and rather exclusive, the community chose to remain on its

own for hundreds of years until the government tried to gently draw it

into the mainstream of national life.

|

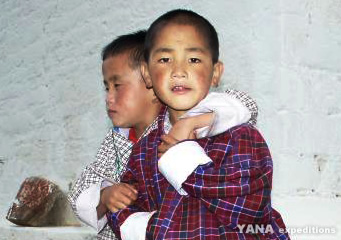

HM Queen Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck

and

HRH Ashi Kesang Wangmo Wangchuck |

| The

establishment of the community school at Sengdhen in 1987 has proved a

significant step in the direction of weaving the Lhop community into the

collective Bhutanese consciousness. The personal initiative of Her Majesty Queen

Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck and critical inputs of the Tarayana

Foundation have been instrumental in bringing the community into the

national fold. |

|

As

dawn breaks and the whistle blows, the 393 boarders scurry and scramble

towards the lone water-tap that feeds the 500 plus school population.

A quick splash on the face and the little ones run, tying their belt and

pulling the gho as morning study begins. A round of supervised study, some

cleaning and it is time for breakfast.

| As

Jigme Tshering's steaming phikka (black tea) irrigates his soya

power, the vapours mingle with those of the dew-soaked dust as it receives

the first light of Sengdhen's Autumn sun.

Wet

or dry, warm or cold, the near-end of the football field is the dining

facility for the biggest boarding community primary school in the country.

But Jigme and his friends sit, stand and squat as they roll soya-flour

into a ball and relish a sip of phikka as they attend to the next impending

bell.

Eight

o'clock and this is assembly time. All the 485 students and six regular

teachers plus three apprentice teachers and a non-formal education teacher

are in attendance, barring a few. The sound of coughing and signs of

cold are all too obvious. Many feet are bare. |

|

|

Ordinary

slippers are the order of the day. There are two speakers this morning.

Jagat Bhujel aims to be a teacher after finishing his studies. He extols

the value of education and the role of teachers. Tshering Dema highlights

the importance of the national language and the need to promote it in her

confident Dzongkha.

As

the captain calls the house to order and unfurls the national flag, the

best part of the assembly is, of course, the singing of the national anthem

which resounds in the little village and immediately connects everybody

to a bigger reality and a sublimer entity.

Sengdhen

becomes Bhutan. The classrooms are minimally furnished and the facilities

are spartan. The walls are a sparse text of mathematical symbols, science

formulae, grammatical rules, some proverbs, poems, and health messages

and teaching aids. The mid-November wind already whistles through the windows

and corridors. The classrooms echo with the sound of learning as teaching

goes on.

| In

isolated Sengdhen, the children's world is essentially defined by the teachers.

They are the only reality beyond the children's family, neighbours and

a few others further afield. That explains why most children do not see

themselves doing anything except becoming teachers in the future.

Whether

it is Sonam Choden or Sherub Dorji or Jigme Tshering of Class I, Sangay

Pema of PP, or Mindu Zam of Class VI, teaching is their life's goal. Only

Santa Kumar sees himself as a doctor and Chal Singh Lama aspires to be

a driver. |

|

|

A

visit to their hostel in the evening will be enough to challenge even the

most robust optimism.

The

batteries of the solar-powered equipment have served the school faithfully,

but replacing the crippled ones has been a proposition too expensive to

afford.

The

best the children do, therefore, is to improvise. But it is improvisation

stretched to its limits. Groups of eight children sit around a low, feeble

kerosene lamp and do their homework or try to goad their eyes to see the

letters. There are smaller groups at times. Some have a half-burnt candle-stick

that rushes to its end in the wake of the night-wind that takes liberties

with the open windows. Others have no resource. They do the next best thing

- huddle up in thin blankets and invite sleep on rough wooden beds. One

cannot but wonder how these children will compete with their peers in better

surroundings in the more advanced centres. There are no secure doors, but

the head-teacher assures that there have been absolutely no untoward incidents

of any kind so far.

It

has been achieving better than average results in all the Class VI examinations

and the pass percentage in other classes is quite high. The cultural and

sporting life of the school is very rich. It was the winner of the inter-school

football and volleyball tournament in Panbari recently. It hosts scouting

and sports events regularly.

"Perennial

shortage of teachers is our biggest problem," longest-serving head-teacher

Kinley Tenzin agonises. "Next is the challenge of transporting over 70

tonnes of food items from Samtse to feed our big family of close to 400

members."

|

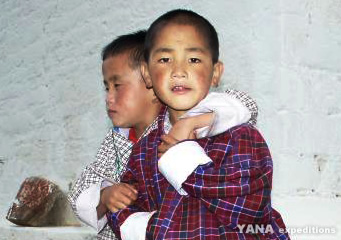

| School girls in Wangduephodrang |

| But

the adversities of difficult places are compensated for in other ways.

Coming from different parts of the country, the teachers have developed

a wonderful culture of cooperation, caring and sharing. They are deeply

committed to the welfare of the children so evident in the many ways they

relate to and look after the children many of whom are as young as seven

years of age, yet stay in the hostel. |

|

"Teaching the children of this remote

place is both a joy as well as a challenge" to Siwan Rai, who has been

here for over six years. "The innocence of the children and their respect

are unforgettable" for others.

For

70-year old Mongal Dhoj Rai, who donated the land to build the school and

the upcoming lhakhang, the coming of the school to their locality has provided

"eyes to the community". Dorji Doya is "deeply grateful to the government

for giving us a school in our poor community".

Some

331 students have graduated from Class VI since the school admitted 108

children in PP in 1987. The non-formal education programme has made its

own critical contribution. The teachers are convinced that the advent of

the school has brought about visible changes in the general life of the

Lhop community.

|

|

School

in Haa |

Events

like the celebration of our national foundation day or the birthday of

His Majesty the King are much-anticipated occasions. The whole community

converges on the school grounds to partake of the joy of the celebrations

and to be part of the larger idea that is the nation and the symbols of

our national life. Sengdhen Community Primary School has been a bulwark

for fostering a sense of national consciousness in this fabled part of

this land.

| Contributed

by Thakur Singh Powdyel for KUENSEL, Bhutan's national newspaper, 2006 |

|

top

|

Links |

|

|

|

External

links |

|

TARAYANA

FOUNDATION

|

|

|