|

Bhutan's Religion Bon |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

| Bon, Buddhism or both - What do we Bhutanese believe? |

|

|

| While

we in Bhutan may be Buddhists in faith, it seems that we are more Bon in

our daily rituals. In the past, because of our lack of understanding of

Bon, we simply relegated it to the villages (of earlier Kuensel article

written by Rinzin Wangchuk), where animals were sacrificed and Yul lhas

worshipped. But Bon actually constitutes more than that.

"Bon:The Magic Word - The Indigenous Religion of Tibet", an ongoing exhibition

at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, is the world's first exhibition

ever on Bon. |

|

.

|

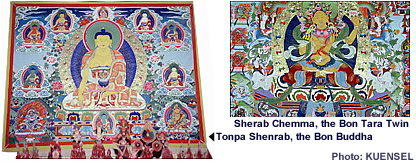

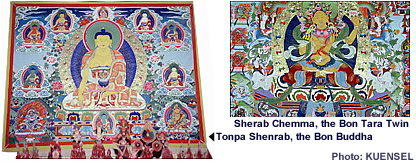

| To

a viewer, the showcased pieces of art are no different from Tibetan-Buddhist

paintings. But a picture of what may be (or look like) Buddha Sakyamuni is actually Tonpa Shenrab, Bon's founding father. A painting of what may

resemble the Tara is the Bon goddess Sherab Chemma. The differences are

so slight that it takes a Bonpo or Buddhist expert to recognize them. |

|

Jeff

Watts, Director and Curator for the Himalayan Art Resource, says that some

ways to identify Bon art would be to look for distinctive symbols, objects

and the number of disciples or attendants.

The

Buddha is usually depicted with two, while Tonpa Shenrab has four or more

figures. The latter is also shown sometimes with a sceptre and a lotus hat beside him.

|

Tonpa

Shenrab, the Bon Buddha look-alike |

|

|

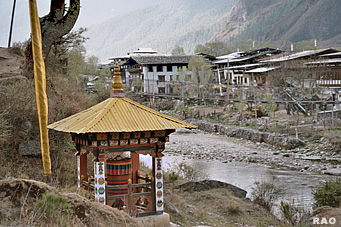

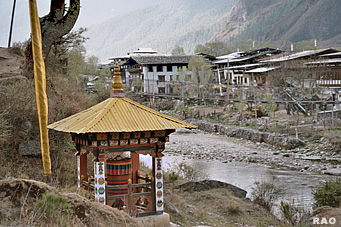

Tshog offering on altar/terrace at Halong

|

Hand

gestures also help. In the Bon meditation posture, the left hand is placed,

palm up, over the right hand, which is also depicted palm up.

In

the Buddhist tradition, it is the reverse. But Bon artists weren't always

consistent with these depictions and that adds to present day confusion.

Rainbows and indigenous animals of Tibet like the otter, bear, yak, wild

ass (kyang) and bamen are also said to be more common in Bon art.

|

|

The

overall similarity in the styles speaks for the history of the two religions

and how each influenced the other over centuries, leaving much of the Buddhist

regions in the Himalayas with a unique and colourful strand of Buddhism.

But while the arts and traditions may appear to be alike - Bonpo nuns and

monks wear red robes, have lamas and monasteries just like Buddhists do

- there are fundamental differences.

Buddhists

attribute their teachings and philosophy to the historical Buddha from

India and revere him above all deities in the Buddhist pantheon. The Bonpos,

however, believe that Bon philosophy, similar to Buddhism, was actually

taught by Tonpa Shenrab. In fact, because Bon predates Buddhism's advent

into Tibet, they believe that the original Buddha was Tonpa Shenrab and

not Buddha Sakyamuni. Bonpo's also circumambulate their temples anti-clockwise

and all their lamas are voted into their positions, unlike Buddhist ones,

who are reincarnated. Today there are an estimated 2 million Bonpos, whose

beliefs and practices have little to do with Buddhism.

So

how are we more Bon in practice?

The

answer seems to vary between Bonpos and Buddhists and their claims on the

sources of ritualistic traditions and who influenced whom with what. Dasho

Sangay Wangchuk, advisor to department of Cultural Affairs in the Home

Ministry, acknowledges that Buddhist practice in Bhutan has had an overpowering

influence from Bon. "In my opinion and from my observations, the influence

has been great. Although Buddhism is our faith, I think many of our rituals

are not only derived from Bon but are based on Bon beliefs," he said.

|

| Many

ritual objects we use and think to be Buddhist originate from Bon. Research

and studies on the subject seem to support this. Prayer flags, tormas (sacrificial

food offerings), use of swords, spears, and arrows in rituals, namkhas

(thread-cross constructions), belief in lus (underworld spirits), yulhas

(village deities), and nyes (spirits that live in trees, rocks, lakes and

mountains), are all Bon traditions. Even our endless worldly rituals to

local deities, observed to clear obstacles, to bring wealth, to make the

sick better, pawos, mo and tsi all come from the Bonpo cosmogony. Our death

rituals also stem from Bon and the practice of Phowa comes from their soul

ritual.

Gyeshe

Samdrup Dorji is a Bonpo Gyeshe from the Bon Menri monastery in India.

He is a student of Menri Trizin, the highest Bonpo Lama today. Gyeshe Samdrup's

mother is a Bhutanese and, while visiting her in Bhutan a few years ago,

he came upon a monastery in the district of Wangduephodrang called Shaa

Sidpai Gang. He was curious since Sidpai Gyalmo is the arch Deity for the

Bonpos. |

|

"I

made some enquiries and I found that the local deity was indeed Sidpai

Gyalmo. I was very surprised to discover that. It seems that Bon is very

much there," he said. According to him Bonpo texts also claim that a Bonpo

Dzongchen master, Shanshung Nyenju, meditated at Taktshang long before

Guru Rinpoche made it famous.

The

most controversial of all practice and beliefs, however, is animal sacrifice.

Gyeshe Samdrup denies it ever had a place in the Bon religion. Most present

day writings about Bon do not mention it. But it is evident that animal

sacrifice - in some cases even human - was a feature of Bon in pre-Buddhist

times in Tibet. B L Bansal, an Indian writer, confirms this in his book,

"Bon: Its Encounter with Buddhism in Tibet".

|

| "Sacrifice

of animals to propitiate gods was an important feature of the old Bon religion,"

he says. "Such sacrifices were performed in state ceremonies. Sheep, dogs,

donkeys, horses, yaks, and sometimes, even human beings were sacrificed

to please the gods." |

|

According

to Bansal, vivid descriptions of such practices can be found in Bon texts

like gZer myig.

"If

animal sacrifices taking place in some Bhutanese villages are said to be

Bon, then I don't know what they are practising," Gyeshe Samdrup said.

But Khenpo Tenzing Norgay, a Bhutanese student of Penor Rinpoche, said

that this was the practice of Bon Nagpo. There are two kinds of Bon, he

said, Bon Karpo and Bon Nagpo. "The Nagpo entails black magic and animal

sacrifice. It is an outdated practice. Present day Bon is associated with

Bon Karpo, which is similar to Buddhism and certainly does not entail these

practices." According to Kuensel, a Kasho was issued several years ago

by the Je Khenpo to stop animal sacrifice.

So

how did it come to be in Bhutan in the first place? One theory is that,

when Buddhism came to Tibet in the 7th century, King Song Tsen Gampo's

court readily embraced it. Bonpos, who were then socially discriminated

against because of their pagan beliefs, were persecuted and forced to convert.

Those who didn't fled and settled in regions across the Himalayas where

their traditions were conserved. Meanwhile, Bonpos who remained in Tibet

found ways to practice by masking their religion with influences from Buddhism.

Simultaneously Buddhism also borrowed from Bon. This was the beginning

of the assimilation we find today.

| Contributed

by Sonam Wangmo, special to Kuensel, Bhutan's National Newspaper, 2008 |

|

| Information on Bhutan |

|

|