|

Bhutan Festivals |

|

|

Bhutan Festivals |

|

|

|

| TSHECHU (RELIGIOUS FESTIVAL) |

| The

Role of the Atsara |

|

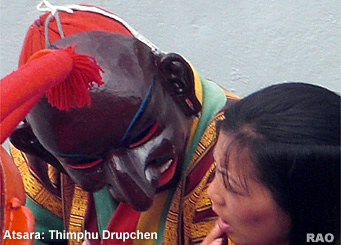

Sandwiched

between two large tourists at the Trashichhodzong courtyard in Thimphu,

the familiar atsara face with a permanent grin brandishes a wooden phallus,

rests it on the head of a young girl and says: "May you be blessed with

nine boys."

"Nine

is too much," reacts an elderly observer. "Then let it be 11 so that you

can have a football team." The crowd bursts into laughter as the man in

the mask leaves to help a hunchback find a place to sit.

|

| Tshechu Mask Dance |

| The atsaras are the clown figures who entertain the crowds at tshechus. But their role

and significance transcends entertainment. "We are an indispensable part

of the tshechu," says a senior atsara, or atsara gom (senior), played by

a student of the Royal Academy for

Performing Arts (RAPA). "There is a world of meaning to the atsara

figure and we have a big responsibility."

According

to Phub Gyeltshen, they should have mastered all the mask dances. "As the

atsaras should correct the dancers if they make mistakes he should know

the sequence of the dances and all other rituals in between the mask dances

or associated with the dances," he explained. |

|

The

atsaras have multiple roles, according to Chencho of Chang Olakha in Thimphu.

The 65-year old, who has played as an atsara for 12 years, said the atsaras

also explain the meaning of mask dances to spectators, entertain them when

dancers are in the changing room, and help control the crowd.

|

| Atsaras |

| From

the eight atsaras at the Thimphu tshechu,

four are selected from the geogs and four from RAPA. Although atsaras from

the villages are not professional dancers they help the dancers by tying

their mask threads, adjust falling dance robes, and even find missing children. |

|

Atsaras

also perform the Atsara Ngon Cham on the last day of the Tshechu.

According to Phub Gyeltshen, the dance is an interpretation of the resurrection

of legendary hunter Sharop Gyem Dorji. "Through the dance it teaches people

that even the most sinful is enlightened if he follows the path of Buddha's

teachings," Phub Gyeltshen said.

The

term atsara, according to Bhutanese scholars, is derived from the Sanskrit

word Acharya (holy teacher) called dubthop in Dzongkha.

top

| The

Legend of the Atsara |

|

Legends

say that about 84 dubthops (Mahasiddhas), who had extinguished all

defilements and afflictions, roamed the universe to subdue evil thoughts

by mocking at worldly things.

Colourfully

dressed, eccentric in behaviour, and even vulgar and abusive in language,

the dubthops used their wit and tricks together with their powers to uproot

evil from the minds of mortals.

"The

atsaras today represent these learned and saintly beings," according to

a scholar, Dasho Lam Sanga. "The dubthops cultivated detachment from mortal

feelings like embarrassment, hesitation, and reservation, as such they

appear in these forms and are always vulgar."

Dasho

Lam Sanga said that atsaras also symbolised spiritual protection. The balloon

and the wooden phallus, which the atsara holds are symbols. The balloon

represents the swine bladder, which the dubthops used to collect diseases

sown by demons. The wooden phallus symbolises the genuine accomplishment

of wisdom by the dubthops, and the tang-ti (rattle), represents khandoms

(consort) of the dubthops. Atsaras from the villages have their

own interpretation. According to Chencho, the four masks they wear symbolise

the four protective deities of the Thimphu valley. The

red mask is the Dorji da-tse, blue

is the Yeshey Gonpo and other

two are the Geynin Bjakpa Mila of Dechenphug and the Dungla Tsen.

Atsaras

feel spiritually lifted and happy performing their roles during the three-day

Tshechu although sometimes they have to face uncomfortable situations in

response to their lewd and vulgar comments. "It's a part of the tradition,

but people don't understand," said Chencho.

"Atsaras

do not respect time and place," a young student said. "It is embarrassing

when you are with your parents and atsaras come with their vulgar jokes."

Today

atsaras are also criticised for asking for money during the tshechus. Although

atsaras claim that this was a part of the tradition, a new rule now allows

the atsaras to collect offerings only during the last day of the tshechu.

On an average an atsara collects about Nu.10,000. Chencho collected Nu.14,000

last year.

"They

are a wonderful part of the Tshechu," a tourist, Marsha Davis, said. For

Lil Laidlaw from Montana, United States, who boasts of an atsara mask back

in her room in Montana, atsaras keep the tshechu alive.

top

| The

Atsaras at the Thimphu Tshechu |

|

|

| Tshechu Mask Dance |

|

They

can be witty and wry, lewd and salacious, annoying and bothersome, but

without them a tshechu would be tame.

The

Atsara, in his the wooden mask with a crooked red hawkish nose and a permanent

grin, and commonly seen as the jester of the tshechu, is more than the

mask depicts.

Atsara

is derived from the Sanskrit word Acharya (holy teacher) or dubthop

in Dzongkha.

|

|

According to religious history, about 84 dubthops (Mahasiddhas),

who had extinguished all defilements and afflictions, roamed the universe

to subdue evil thoughts by mocking worldly things.

Weirdly

dressed, whimsical, vulgar and abusive in language, the dubthops used their

wit, foolery, and drollery, together with their powers to uproot evil from

the minds of mortals.

Atsaras

today represent these learned and saintly beings. Their apparent vulgarity

arises out of their detachment from human feelings like embarrassment,

hesitation, and reservation.

At

2007's Thimphu tshechu 29-year-old Tsagay, a student of the Royal Academy

of Performing Arts (RAPA), is the Atsara gom (head Atsara).

Tsagay,

a father of two children, calls himself an artiste. "It is no joke being

an Atsara at the tshechu," says Tsagay. "Without mastering all the mask

dances, you cannot become the head Atsara. It is an art."

According

to Tsagay, Atsaras are spiritual figures at the tshechu, who carry the

blessings of mask dances, and, through the auspiciousness of the day, can

heal or cure.

Dorji

Wangmo, 63, never misses receiving wang (blessing) from the Atsara.

According to the farmer from Kabisa, the lewd remarks and outrageous behaviour

of Atsaras when they come to bless people is a test in itself. "It is way

to test if people are ready to embrace religion in all forms," she said.

Dawa

Nob is another Atsara at the tshechu selected from Thimphu's Toeb gewog.

"We have a big responsibility," he said, waving a wooden phallus. "We are

the guides here for the mask dancers and also for spectators. We explain

the meaning of the dances and correct any mistakes in the dance steps."

This

year, on their own initiative, the Atsaras decided to promote the use of

contraceptives. "If you use condoms, you will live long," an Atsara explained

in English to a group of tourists. "Yes," the tourists agreed.

"It's

a good opportunity to educate people because they are not embarrassed listening

to an Atsara," he said.

Most

spectators see Atsaras as entertainers in an otherwise formal festival.

"The first thing that comes to mind when we talk of a tshechu is an Atsara,"

said Choki Lhamo, a student. "I don't mind their dirty jokes as long as

they keep them within limits," she said.

"I

love them," said Mark Beltzman a tourist from the US, "They are a great

transition between the dancers. We should have more of them."

But

Atsaras also face awkward situations when women react angrily to their

lewd jokes. "Sometimes they do get excited and grab us," said a woman spectator.

| This

article was contributed by Ugyen Penjore, KUENSEL, Bhutan's National Newspaper

2007 |

|

| Information on Bhutan |

|

|