|

Bhutan's

Festivals |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

Mani

sum: the sacred songs of Talo Tshechu

|

It

is a chilly morning but 64-year old Rinchen Dema is perspiring and panting.

She has been walking for an hour carrying a bulky lunch pack from her village,

Botokha, nearby Talo.

|

| It

is the second day of the Tshechu in Talo - the seat of the mind

incarnations of the Zhabdrung.

Rinchen

Dema settles in a corner and waits for her favorite programme - the Zhungdra

(classical song sung in meditative style without music) performance

by the Talo dance troupe. |

|

|

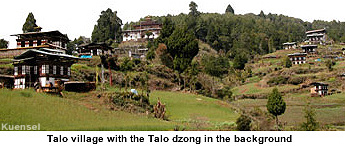

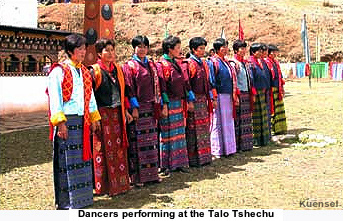

Talo

Tshechu |

|

|

| "Very

soon my legs will not be able to carry me to this ground," says Rinchen

Dema, once a member of the Talo dance troupe for 16 years, as she prepares

to spend the day in Talo.

The

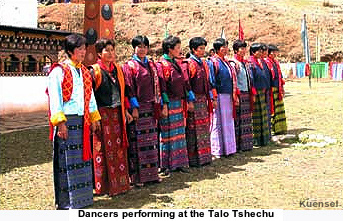

three-day Talo Tshechu is well known for its mask and Atsara dances,

but an equally popular attraction with deep religious and historical significance

is the Zhungdra by the Talo dance troupe. |

|

"The Zhungdra

performance particularly three songs known as Mani Sum are very close

to the heart of the Talops," says Bhutanese traditional dance master,

73 year-old Ap Dawpel.

Probably

the only dance master alive to retell the importance of the Talo Zhungdras,

Ap Dawpel says that the Mani Sum was composed by Meme Sonam Dhondup,

the grandfather of Zhabdrung Jigme Chogyal

(1862-1904), the fifth mind reincarnation

of the first Zhabdrung (1594-1651).

The

three songs of Mani Sum are performed at the closing item on each

day of the three-day Tshechu. Samyi Sala is performed on the first day,

followed by Drukpai Dungye on the second day and Thowachi Gangi

Tselay on the third and last day.

According

to Ap Dawpel, Zhabdrung Ngawang Choegyal in his last words (Sung

Chem) requested his younger brother Mepham Kuenga Dra to perform

the mask dances and the songs composed by his grandfather every

year during the Talo Tshechu. Samyi Sala was composed when

the Talo Sanga Choeling Dzong was built. "The inspiration to build the

Talo Dzong was drawn from the Samyi monastery in Tibet. Talo was

then compared to the Samyi monastery," Ap Dawpel says. Drukpai Dungye tells

the story of the Zhabdrung lineage, and Thowachi Gangi Tselay is

the thanksgiving or the Tashi Deleg song.

Another

notable Talop song is the Drongla ya ya, which was composed by Zhabdrung

Jigme Choegyal's father, Kencho Wangdi. The song praises in detail

the Talo monastery from the cobblestone flooring in the courtyard to the

ladders that reach to the seat of the Zhabdrung.

The

songs have passed down from generation to generation without the slightest

change in tune and lyrics, according to Ap Dawpel. "It is close to the

heart of the Talops because it is like a priceless inheritance and has

been blessed by many great Lamas," he adds. The songs, hand written on

ancient scrolls, are registered as a property of the Talo monastery.

"Very

soon my legs will not be able to carry me to this ground," says Rinchen

Dema, once a member of the Talo dance troupe for 16 years, as she prepares

to spend the day in Talo.

The

three-day Talo Tshechu is well known for its mask and Atsara dances,

but an equally popular attraction with deep religious and historical significance

is the Zhungdra by the Talo dance troupe. According to Ap

Dawpel, Meme Sonam Dhondup first taught the Mani Sum to his

two younger sisters, Aum Kaka and Tshering Lham. Ap dopey recalls his parents

telling him that the two sisters took about two weeks to master the songs

and the steps of the accompanying dance. "The steps might appear simple,

but it takes months to perfect the movement," says Ap Dawpel.

|

| Tsepoem

(dance leader) Kinzang Om agrees. The 40-year old dance leader who

started dancing at the age of 17 says that one perform the Mani Sum in

two weeks but without the subtle nuances. "I have been singing and dancing

for the last 23 years and I still need to practice the Mani Sum," she says.

One

unique feature of the Talo Zhungdras is that only the Talops are allowed to learn the songs. "The songs are blessed and people from

other places other than Talo will find it difficult," Ap Dawpel says. "If

not performed properly it can bring misfortune in the form of natural calamities

and outbreak of diseases." |

|

According

to a village elder the women of the dance troupe must refrain from sexual

intercourse three days before the Tshechu to maintain the sanctity of the

Tshechu. Others say that learning, dancing, and singing these songs has

become an obligation for the Talops who are one way or the other linked

with the various incarnations of the Zhabdrungs.

According

to Kinzang Om, she gets a spiritual satisfaction from being part of the

age-old tradition. "It is a big responsibility for the Talops and we enjoy

shouldering our responsibility," she says. Another dancer feels that learning

and performing the Mani Sum was a way to honour ancestors and keep alive

an important tradition.

The

troupe starts practicing 16 days before the Tshechu with a daily allowance

of Nu. 30. According to Tsepoem Kinzang Dem, new comers in the troupe cannot

untie a single knot of the song in 16 days. "I have tried to teach some

dancers from other places and they find it very difficult. I think these

songs are meant only for Talops." "The Talops are known for their

excellence in the Zhungdra," says Aum Ugyen Dem, a villager from

Lobesa, "They are known for their rhythm, voice and the steps." While the

Talops take pride in their rich tradition, veterans like Ap Dopey and Kinzang

Om are worried by the growing influence of modern Bhutanese music.

Even

the Talo Tshechu is changing according to Ap Dawpel. The songs are

now performed outside the dzong and the number of dancers has increased

to 11 from seven, Boedra (lively folk songs originally performed by

Boegarps or court attendants) has been introduced, and people crave

for Rigsar (modern Bhutanese songs) during the Tshechu.

The

veteran has another concern. "There will be no one to retell the story

of the songs," he says. "Rigsar, which is more appealing to the youth will

take over and these songs will only be a history."

On

his part Ap Dopey attends the Talo Tshechu every year and personally coaches

the troupe and monitors the mask dance practice before the Tshechu.

|

| Kinzang

Om fears that one day there will be no dancers during the Talo Tshechu.

"All the girls are now going to school and show little interest in these

kind of songs," she says. "The government should intervene to help this

tradition alive for ever."

According

to the principal of the Royal Academy

for Performing Arts (RAPA), no research has been done because these

songs were registered under the Thram of the Talo monastery. |

|

The RAPA dancers

do not know how to perform these songs. "We made research attempts, but

we were told that these songs were not for public entertainment," Principal

Thinley Jamtsho said.

"These

songs are performed only during the Talo Tshechu and if RAPA performs

it everywhere, the blessings would be lost," he added.

However,

a Bhutanese ethnomusicologist, Jigme Drukpa of the academy has been following

Ap Dopey to the Tshechu to study the songs and dances.

Back

in the corner of Talo dzong, Rinchen Dema is least bothered by the afternoon

wind. She hums along with the troupe as she prepares to leave satisfied.

"I prayed to come back safely next year," she says as she tries to recollect

a few lines from her favourite number, Drongla ya ya.

|

| Contributed

by Ugyen Penjor, Kuensel |

|

2005

| Talo

is in Punakha valley and it used to be closed to visitors. Some of the

Travel Agents had promoted Talo Tshechu and they had problems since they

were not allowed to take guests to the festival. |

|

| Information on Bhutan |

|

|