|

Dzongkha:

Bhutan's national language

|

|

Bhutan's

Culture: Dzongkha |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

The

history of the Development of Dzongkha dictionaries

|

|

|

| The

publication of three Dzongkha dictionaries in 2000 will definitely

encourage efforts to develop the national language. The English-

Dzongkha Dictionary (By Kunzang Thinley and Tenzin Wangdi: KMT Printers;

413 pages. Nu 225) and My Picture Dictionary (By Garab Dorji: |

|

World

Wildlife Fund; 73 pages. Nu.200), which is yet to be released, are,

in their design and purpose, new developments in the history of Bhutanese

lexicography.

The

Dzongkha-English Dictionary, which will be published by the Dzongkha Development

Commission (DDC) by the end of 2000 will have over 10,000 entries.

But the Choeked-Dzongkha Dictionary, being compiled by Geshe Tenzin Wangchuk,

a researcher at the DDC, will be the most comprehensive and authoritative

one. It will have over 100,000 entries.

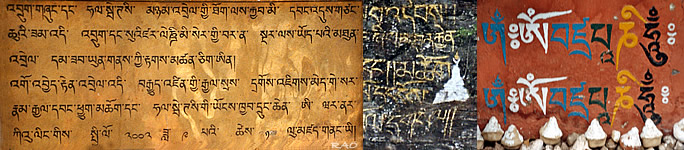

The

Choeked-Dzongkha Dictionary will be a landmark in the history of Bhutanese

lexicography. Vernacular Dzongkha has been spoken for hundreds of years

in the country, often with dialectic variation in Haa, Paro, Thed (Punakha)

and Wang (Thimphu). There are instances of vernacular Dzongkha writings

dating back to the 17th century as reported in a document, which

will soon be published by the DDC. However, it was only in 1961 when the "first systematic efforts were undertaken to 'modernise' and codify

the national language".

It was in the same year His Late Majesty

Jigmi Dorji Wangchuck decreed Dzongkha as Bhutan's national language. Before

Dzongkha, Choeked was taught in modern secular Bhutanese schools, even

until 1971 due to the unavailability of Dzongkha materials. The

breakthrough came when the Dzongkha Division of the Education Department

started developing Dzongkha materials.

The

first serious Dzongkha Dicitionary was published by the Text Book Division

of the Education Department in 1986. It was compiled by Kunzang

Thinley, the co-author of the new English-Dzongkha Dictionary, and Choki

Dendup. The year really marked the beginning of dictionary compilation

in Bhutan. Before that, the development of Dzongkha grammar, manuals and

guidebooks assumed greater importance. In fact Dzonkha grammar was extremely

necessary to differentiate the evolving written Dzongkha from Choeked.

The New Method Dzongkha Hand Book published in 1971 and written

by Bhutan's contemporary scholars like Lopen Nado, Lopen Pemala and Lopen

Sanga Tenzin were used for many years in schools in Bhutan. There

were attempts to develop grammar, dictionary and manuals in Sharchop all

along. Pastor Ralph Hofrenning wrote the first manual of Sharchop grammar

in 1955. According to him, 'it is the firstgrammar ever attempted in Gongar,

an unwritten language of the far east'. Dasho Tenzin Dorji's unpublished

Thongwa Zumshor is a Choeked-Sharchop manual. The latest one is perhaps

Susanna Egli-Roduner's Handbook of the Sharchokpa-Lo/Tsangla published

in 1987.

|

An

interesting development however, was the compilation of an Anglo-Bhutanese

Dzongkha by Fr. Phillip S.D.B, principal of Don Bosco Technical School,

Phuntsholing in 1971. In absence of Dzongkha typewriters, all typed English

entries were followed by meanings in Dzongkha, which were laboriously written

in longhand. This perhaps is the first bilingual dictionary in Bhutan.

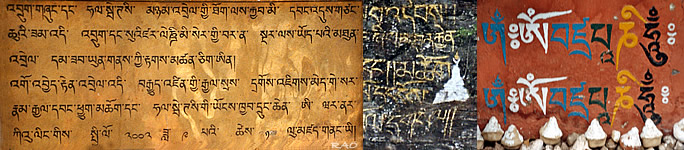

Choeked

is the basis of written Dzongkha, and therefore, Dzongkha dictionaries,

in their origin heavily rely on Choeked. Lam Choechong's Choeked-Dzongkha

Dictionary (Q-Reprographics, 1997), the first of its kind has 5881 entries.

It is based mainly on the Choeked dictionary of Pelkhang Lotsawa written

in 1538. Pelkhang Lotsawa was a disciple of the Eighth Karmapa Michoe

Dorji.

The

Dzongkha Dictionary, published by the DDC in 1993, is the largest

so far, with a total of 7932 words. This and the one published in 1986 are the only two Dzongkha dictionaries. Rinchen Khandu's Dzongkha-English

Dictionary is perhaps the first dictionary that uses Dzongkha romanization.

Romanzation of Dzongkha was officially adopted in 1991. It therefore, addresses

audience, especially foreigners who wishes to learn Dzongkha. But there

were already manuals and guidebooks, which either used romanization or

phonological transcription, intended to teach Dzongkha to foreigners.

A

Guide to Dzongkha in Roman Alphabet written in 1971 by Lt. Rinchen Tshering

(RBA) and Major A. Daityar (IMTRAT), A Manual of Spoken Dzongkha by Imaeda

Yoshiro and Dzongkha Rabsel Lamzang published by the DDC in 1990 are a

few examples. Those who want to learn Dzongkha will find the two new dictionaries

helpful. However, there are many distinctions between them, the foremost

being what each title suggests: an English-Dzongkha dictionary and a picture

dictionary. They are thus very different in style, presentation and content

as well. The former has 2120 entries in Dzongkha and 1705 in English. In

it, the meanings of words are not given but the words themselves are used

in the sentences that follow.

The

meanings in Dzongkha are then given, again followed by sentences. Its major

drawback is the assumption that users know meanings of words either in

Dzongkha or English and would be able to read the other to understand its

corresponding meanings. It requires users to have a good command of both

English and Dzongkha. It is currently being reviewed by the CAPSD, Education

Division to consider its usage in schools. With an entry of over 600 words

and pictures and illustrations, My Picture Dictionary is especially designed

for children. Beginning with family members, it covers forty three different

subjects which includes colours, dresses, every day objects and materials,

birds and animals, fruits and vegetables, seasons, games, monasteries and

others.

Garab

Dorji, a grade XII student, has done all the illustrations and paintings

himself. It is primarily a Dzongkha-English dictionary. Both the

dictionaries are the first of their kind and available only in paperback

editions. Just as creative writings, compilation of dictionaries also appears

to be growing in Bhutan. Tashi Tshewang and Namgay Thinley are developing

a Dzongkha-English dictionary with a totally different approach. It would

also have over 10,000 entries.

| Contributed

by KUENSEL, Bhutan's National Newspaper 2000 |

|

| Information on Bhutan |

|

| Links |

|

|

|

External

Links |

|