|

Bhutan History |

|

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

How

Europe heard about Bhutan

|

When

did Bhutan first appear on a western map? When did Europe first become

aware of Bhutan's existence?

|

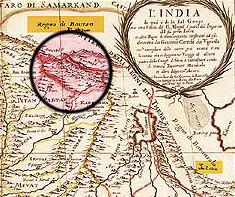

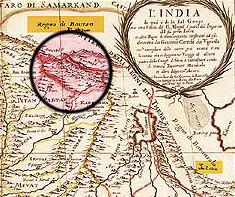

The 1683 map by Cantelli which sparked Dr Gandolfo's investigation

| With these questions in mind, Dr Romolo Gandolfo,

an Italian history lecturer and newspaper editor now based in Greece, decided

to start investigating the issue by paying a visit to the largest map shop

in London two years ago.

After

hours of digging in the shop's drawers, he suddenly came across a map of

Northern India dated 1683 in which a 'Regno di Boutan' (kingdom of Boutan)

stood where one would expect to find today's kingdom of Bhutan. |

|

Presenting

a paper on Bhutan and Tibet in European cartography: 1582-1800 at the international

seminar on Bhutan studies, Dr. Gandolfo said that many elements in this

map, drawn by Italian geographer, Giacomo Cantelli da Vignola, baffled

him. For example, Nepal appeared not once, but twice, and in quite distant

places. Boutan was plotted north of, rather than south of, Mount Caucasus,

as the Himalaya was known in Europe during the 17th century. Besides, the

only Europeans known to have visited Bhutan by that time (the Jesuit fathers

Cacella and Cabral, in 1627) had written that the country was variously

called Cambirasi, 'the first Kingdom of Potente', or Mon. If so, where

did the Italian cartographer get the name Boutan from?

Dr

Gandolfo points out that Cantelli's main source was The Six Voyages into

Persia and the East Indies, a best-selling travel book written by Jean

Baptiste Tavernier, one of the richest and most famous European merchants

in Asia. In this book, first published in French in 1676, Tavernier has

a section titled "The Kingdom of Boutan"in which he explains that this

mysterious country was very large and distant from India; that it is located

beyond the mountains of the Raja of Nupal (Nepal); and that it was frequented

by rich merchants coming from places as far away as the Ottoman Empire

or the Baltic Sea. Tavernier then goes on to describe the 'King of Boutan',

saying that 'there is no king in the world who is more feared and more

respected by his subjects, and he is even worshipped by them.'

Anyone

familiar with the geography and the history of the Himalayan region in

the middle of the 17th century, argues Dr Gandolfo, should be able to recognise

that Tavernier is here describing Tibet and the Dalai Lama, rather than

Bhutan and the Zhabdrung. Clearly, the Kingdom of Boutan that appears

in Cantelli's map is, in reality, Tibet. In other words, Boutan was

an alias, a synonym, for the whole of Tibet, a name in use across Northern

India, from Kashmir to Bengal. Unfortunately Tavernier never mentions Lhasa

as the capital, thus making Cantelli and other European map makers unclear.

|

| Names

similar to Boutan (Bottan, Bottanter) had begun to appear in Europe

as early as the 1580s in reference to a large country north of India,

where a pious and light-skinned mountain people was said to live. |

|

A description of this newly discovered nation (the 'Bottanthis') appeared

in a book and a map published in Italy in 1597. Many Europeans thought

that the Botthantis might be the lost Christian nation of Prester John,

a mythical priest/king who, according to medieval lore, lived somewhere

in the heart of Central Asia. It was the hope of reestablishing a contact

with this forgotten Christian people that drove a score of Jesuit fathers

into Tibet and present-day Bhutan in the 1620s.

From 1700

till the 1770s the term Boutan appeared on several important European

maps of Asia as an alias for the whole of Tibet (or of the 'Kingdom of

Lhasa'). The most important and detailed of these maps (published in 1733)

is even titled "General Map of Thibet or Bout-tan". Despite the fact that,

during the first half of the 18th century, a group of Italian missionaries

resided in Lhasa and wrote many reports and letters back to Europe in which

they clearly mentioned present-day Bhutan under several native names, these

documents apparently disappeared in the archives and never reached the

map makers. Or, if they did, they were discarded for lack of reliable geographical

details.

Until

the 1770s, present-day Bhutan failed to appear on European printed maps.

It did appear, however, under the name of 'Broukpa', in a beautiful sketch

map drawn around 1730 by Samuel van Putte, a Dutch "explorer"of the early

18th century who travelled alone across all regions of Tibet (but not into

present-day Bhutan). Showing a reproduction of the map, Dr Gandolfo sadly

remarks that the original, kept in a Dutch museum, had been destroyed during

WWII in a bombing.

So,

when did Druk-Yul (also known as Brukpa, Lho Mon) get its present

western name of Bhutan? Only in 1775, says Gandolfo, after Bogle's

trade mission to the Deb Raja and the Panchen Lama in Tashilhunpo. In his

instructions to Bogle, in 1774, Warren Hastings, the Governor General of

the East India Company, still refers to Tibet as Boutan. And Bogle initially

uses the two terms interchangeably.

It

was only after he was detained for four months in Thimphu valley by the

Deb Raja in the rainy summer of 1774 that Bogle developed a clear appreciation

of the specific features - political, cultural and religious- of Bhutan.

Upon crossing the border near Phari, Bogle appears to realise that he was

now in a different country. His long and friendly stay at the Panchen Lama's

court definitively convinced him that he had visited two distinct countries.

When he eventually returned to Bengal, he wrote a final report to the Governer

General in which he formally proposed "to distinguish"the Deb Raja's country

by the name of Boutan and to keep the name 'Tibet' for the large country

on the plateau.

James

Rennell, the first Surveyor General of the East India Company, who had

already plotted part of the Duars, immediately followed his suggestions.

It was Rennell who first anglicised the French spelling Boutan into Bootan.

And it was he who, in his maps, detached Bootan from Tibet, bringing it

down south of the main Himalayan range.

If

Bogle 'discovered and named' Bhutan, concludes Dr Gandolfo, it was

Rennell who, with his numerous and authoritative maps, published between 1780

and 1800, made Europe aware of the existence of this new country. After

that Bhutan was no longer, in Europe's eyes, a be-yul-a hidden country.

| Information on Bhutan |

|

|