The 1 February 2005 takeover of executive powers by King Gyanendra has led to a new era of uncertainty in the tiny mountain kingdom of Nepal. The king now rules the impoverished country of 25 million directly as chairman of the Council of Ministers. The decision by the king to assume direct rule is the latest move by the monarch to undermine democracy in the country. Parliament was dissolved in May 2002 and elections - planned for November of the same year - remain postponed.

Washington criticised the elections, calling them a "hollow attempt to legitimise power" by the king. The political vacuum and lack of elected representatives in government has helped Maoists gain support among many people who feel robbed of democracy and view the king as an antiquated authoritarian figure. As a result, Nepal remains entangled in a three-way fight between the monarchy, political parties and Maoists who say they are fighting to establish a communist state. In November 2005, the Maoists and the parties closed ranks to oppose the monarchy.

The elections returned the Nepali Congress party to power with a simple majority, but fighting within it caused the government to collapse in mid-1993. Elections in November 1994 brought in a hung parliament, with the unified Marxist-Leninist faction of the Communist Party of Nepal becoming the largest party in the new parliament. Six minority and coalition governments of different political hues, combinations and sizes, ruled Nepal between November 1994 and May 1999, when a third general election again returned the Nepali Congress party with a workable majority. Even the post-1999 government was unable to provide a stable administration. Infighting again caused the Nepali Congress to change prime ministers three times in as many years, before the party split in mid-2002. Another incident jolted Nepali politics in 2001. King Birendra, his entire family, and five royal relatives were killed in a bizarre shootout at the royal palace on June 1, after which the present King Gyanendra was enthroned. Frustrated at what he saw as the failure of the political process, King Gyanendra began to reel in the parties, starting with the sacking of the elected prime minister in October 2002. Parliamentary parties condemned the royal move as "unconstitutional" and launched street protests, refusing to join all successive governments except the last one - dismissed by the king on February 1, 2005 - which represented four parties and royal nominees.

Although many Nepalis appeared to agree with the aims of the Maoists - namely an end to the absolute rule of the monarch and the introduction of a more equitable society - their methods soon alienated them from much international and local support. Kidnappings, abductions, killings, rapes, disappearances and taxing the peasantry became widespread, along with a generalised offensive against the state that involved ambushing security forces and bombing district headquarters. Many civilians were killed in these attacks. Then the notion that the monarchy represented continuity and stability, was dashed in June 2001 when a drunken Crown Prince Dipendra wiped out the entire royal family at the Narayanhity Palace, Kathmandu. Prince Gyanendra, the only direct member of The Former Royal Family who survived, was crowned king on 4 June. An investigation said the prince carried out the killings because of a longstanding family dispute over the choice of his would-be bride, before turning a gun on himself.

On

17 November 2005, the Maoists and seven of Nepal's largest political parties

announced an understanding to jointly oppose the monarchy. Though the modalities

for implementing it remain unclear, generally the political parties have

agreed to demand the holding of constituent assembly elections ? a key

rebel demand ? and to the writing of a new constitution. For their part,

the Maoists have agreed to join mainstream politics.

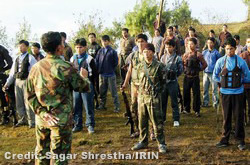

The

government and Royal Nepalese Army are sceptical about the Maoist-declared

ceasefire, saying the Maoists are buying time for military training and

the purchase of weapons.

Some differences between the Maoists and the political parties remain, however, unresolved. One is that the rebels want to appoint a new interim government to hold constituent assembly elections, whereas some of the parties want the last parliament, dissolved in May 2002, restored to oversee such elections. The Maoists extended their ceasefire by a month on 2 December 2005, a move aimed at supporting protests by the main parties to create pressure on the government to work towards peace. The government though had made no peace overtures towards the parliamentary parties or the Maoists by early December. The Maoists have categorically said they will not negotiate with the monarch until democracy is restored. On 7 December, the king reshuffled the cabinet, tasking it to hold February's municipal elections. So in 2006, Nepal faces two differing scenarios: The country's political parties want larger democracy restored first, a tension that could lead to increased confrontation. Alternatively, the outcome could be more peaceful, with a ceasefire and the front formed by the political parties and the Maoists, increasing public demand for peace, forcing even the king to make concessions. Copyright © UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2006 [ This report does not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations] Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN), part of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

|