The last herd, surviving in Shingkhar that belongs to Sonamla, 75, will be grazing in highland of Sephu in Wangduephodrang. Shingkhar was a village known for its strong culture of yak herding, and their livelihood mainly depended on dairy products from the yaks. But ever since the road reached the valley in the mid 1990s, Shingkhar started potato farming and dependence on yaks for a source of livelihood reduced. Shingkhar's vast and lush pastureland is a visitor's delight, and an ideal place to rear livestock. Over a hundred acres of green pastureland surround Shingkhar village, showcasing its serenity and livestock culture. This factor was the main reason for the community's vehement protest against the proposal to use parts of the pastureland for a golf course. Although the last herd of Shingkhar's yaks is to leave, of late, the pastureland has been housing a new herd.

Over 100 tsedar yaks (yaks saved from being slaughtered), were released to graze on the land in Shingkhar. Sonamla, 75, who has lived with yaks since his youth, believes it was some kind of a sign. All these years he did not give in to his children's persistent persuasion to sell yaks and give up yak hearding for a more comfortable life. "We can't convince him, because his yaks are a part of him and herding them part of his life," one of his sons Kuenzang said. Sonamla, however, had to give in to his old age.

"While yaks in summer should be taken to a higher altitude that requires days of walking, I only managed a few hours further from the village last summer," she said. "I have no one at home to look after my parents and children." Tshering Dema said the family did not want to sell the yaks. But it was growing difficult to tend to them. Besides the tsedar yaks only aggravated the problem, because they had to herd the additional yaks, since there was no one to look after them. Tshering Dema said the tsedar yaks posed problems to the existing herd during the breeding season, and rearing them for a lone woman was a major problem.

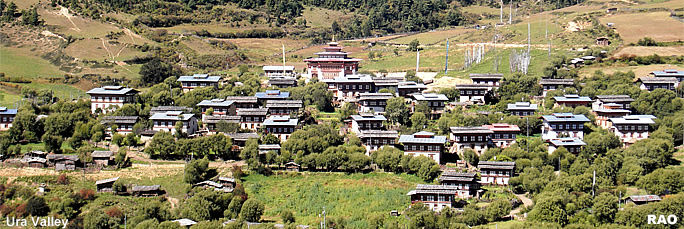

By 2007, yaks in Ura Madrong, the biggest village, disappeared. Somthang villagers sold all their yaks in 2009. Until mid-2011 Shingkhar had two households, including Sonamla's, that still kept yaks. When Sonamla's yaks leave Ura valley this year, a lone villager in Pangkhar will be the last to rear yaks. Records with livestock extension officer in Ura, Phub Thinley, show that of 250 yaks in 2007 in the valley it dropped to 223 in 2008 and 207 in 2009. In 2010, it fell to 180 and to 100 last year; most of them sold to herders of Sephu in Wangduephodrang. He said, Sonamla had about 45 yaks, which once gone some time this year will leave the valley with only about 55 yaks. Of the 40 households in Shingkhar, about 10 reared yaks. Almost all households owned about four to five yaks, which they kept with households that owned more yaks. "Like many age-old customs of livelihood, this one too has become obsolete," a farmer Sonam said. "With education and the pace with which the country is developing, our children will not want to do this." Meanwhile, Sonamla and his daughter awaits the buyer from Sephu to take away their 45 yaks, of which 15 are milking ones that graze on the green pastures of Shingkhar.

|