|

Afrika

- Kenia |

|

|

Afrika

- Kenia |

|

|

Kenia - Umweltatlas

|

|

|

|

Kenia 2009 - Atlas of Our Changing Environment

|

|

|

| Kenya's

chances of realizing its 2030 vision will depend increasingly on the way

the country manages its natural or nature-based assets, a new satellite-based

atlas concludes.

Many

of these economic assets are coming under rising pressure: from shrinking

tea-growing areas to disappearing lakes, increasing loss of tree cover

in water catchments and proliferating mosquito breeding grounds, environmental

degradation is taking its toll on Kenya's present and future development

opportunities. |

|

Thus

improved and more creative management is urgently needed to translate the

aspiration, to the realizing of Vision 2030.

These

are among the key conclusions of the new 168-page Atlas produced by the

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) at the request of the Government

of Kenya.

Kenya:

Atlas of Our Changing Environment was launched by Kenyan Environment

Minister John Michuki and UN Under-Secretary-General and UNEP Executive

Director Achim Steiner.

It

is the first-ever publication of its kind to document environmental change

in an individual country, through the use of dozens of satellite images

spanning the last three decades.

The

request for the Atlas, funded by Norway and supported by the United States

Geological Survey, follows the launch last June in Johannesburg of Africa:

Atlas of Our Changing Environment at a meeting of the African Ministerial

Conference on the Environment.

Mr

Steiner said: "The Kenya Atlas shows both the diversity and the fragility

of the country's natural assets which are at the heart of the nation's

socio-economic development. It highlights some success stories of environmental

management around the country, but it also puts the spotlight on major

environmental challenges including deforestation, soil erosion and coastal

degradation."

"The

Atlas makes a strong case that investments in green infrastructure within

a Green Economy can bring it closer to achieving the Millennium Development

Goals. The Atlas is for the government and for all Kenyans who want to

see transformational change and a path out of poverty to prosperity by

sustainably realizing this country's true development potential," he added.

|

Key

findings of the Kenya Atlas

|

|

Some

of the key findings of the Kenya Atlas include:

-

The nation has increased the proportion of land area protected for biological

diversity from 12.1 percent in 1990 to 12.7 percent (about 75 238 sq. km)

in 2007.

-

The land available per person in Kenya has dropped from 7.2 hectares per

person in 1960 to just 1.7 ha per person in 2005 due to the rapid population

growth of the last few decades. There are now 38 million inhabitants in

Kenya, up from just eight million in 1960. The population is expected to

keep rising, and land available per person is projected to drop to 0.3

ha per person by 2050.

-

Five water towers - Mau Forest Complex, Aberdares Range, Mt. Elgon, Cherangani

Hills and Kakamega Forest - are critical as water catchments, vital for

tourism, and hence towards achieving Kenya's vision 2030.

-

The rivers flowing from the Mau Complex are the lifeline for major tourism

destinations including the Maasai Mara Game Reserve and Lake Nakuru National

Park. In 2007, revenues from entry fees alone amounted to Ksh. 650 million

(US$ 8.2 million at today's exchange rate) and Ksh. 513 million (US$ 6.3

million at today's exchange rate) for the Maasai Mara and Lake Nakuru respectively.

-

A temperature rise of just 2 degrees Celsius would make large areas of

Kenya unsuitable for growing tea, which accounts for 22 percent of the

country's total export earnings. Some 400,000 smallholder farmers grow

60 percent of Kenyan tea.

-

Rapid population growth coupled with conversion of land cover within Lake

Olbollosat's catchment is posing a huge threat to the lake which has periodically

dried up and then come back to life in the past. There is concern that

the increasing number of pressures may mean that if it dries up again,

it could be the end of Lake Olbollosat.

-

The value of soil lost due to erosion in Kenya each year is three to four

times as high as the annual income from tourism. In 2007, earnings from

tourism totaled 65.4 billion Kenyan Shillings (or more than US$ 824 million

at today's exchange rate).

-

Forest loss increases key health risks such as malaria. Research in the

western district of Kisii shows that old natural habitats with a greater

diversity of mosquito predators - such as dragonflies and beetles - have

a lower density of mosquitoes. Intact forests also have less breeding sites

for mosquitoes. Thus conserving forests has multiple economic benefits

from soil stabilization, improved water supplies, more reliable hydro-power

and tourism to health ones including reducing the risk of malaria epidemics.

-

The Cherangani Hills have seen less forest loss than the other "water tower"

forests in recent years and significant areas of indigenous forest remain.

Monitoring and careful management are needed to preserve these valuable

assets.

|

From

Maasai Mara to Lake Turkana - Kenyan ecosystems under pressure

|

|

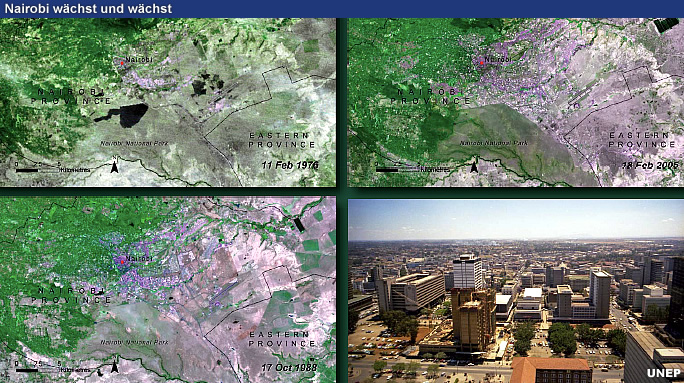

The

Atlas's before-and-after satellite images in this Atlas vividly document

the environmental change in 30 locations across Kenya since 1973 including:

-

The Mau Forest Complex, a key water catchment is being deforested at an

alarming rate due to charcoal production, logging, encroachment and settlements.

One quarter of the Mau forest - some 100,000 hectares - has been destroyed

since 2000.

-

Large scale, uncontrolled, irregular, or illegal human activities like

charcoal production, logging, settlements, and crop cultivation, among

others, caused devastation within the Aberdares range. The construction

of a fence around the Aberdare Range has reduced/stopped uncontrolled,

irregular, or illegal human activities within the forest, as well as human

wildlife conflicts.

-

The Atlas underlines the kinds of economic and environmental choices facing

policy-makers. For example it notes that the vast ecotourism potential

of the Aberdare National Park remains largely untapped, with just 50,000

visitors per year on average.

-

Large mechanized wheat farms in the area surrounding the Maasai Mara have

expanded by 1,000 percent between 1975 and 1995, most of them on the Loita

Plains, significantly reducing the available natural grasslands in this

important habitat for wildebeest - a key economic species in terms of tourism.

-

Between 1973 and 2006, almost half of the natural vegetation cover around

Lake Nakuru, another big tourism attraction not least for its pink flamingoes,

was lost. The satellite pictures show a clear degradation of forest cover

west of the lake, partly due to the excision of 350 square kilometers of

forest in 2001.

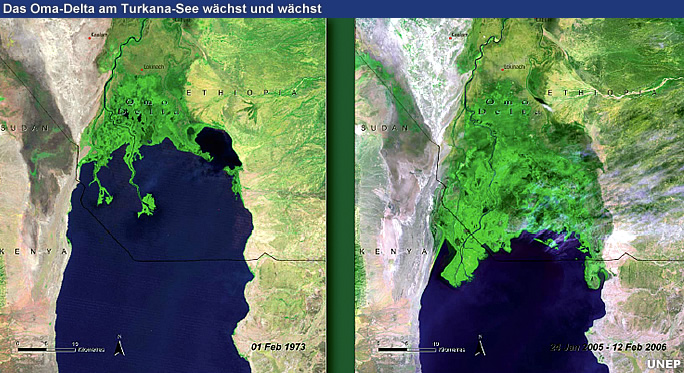

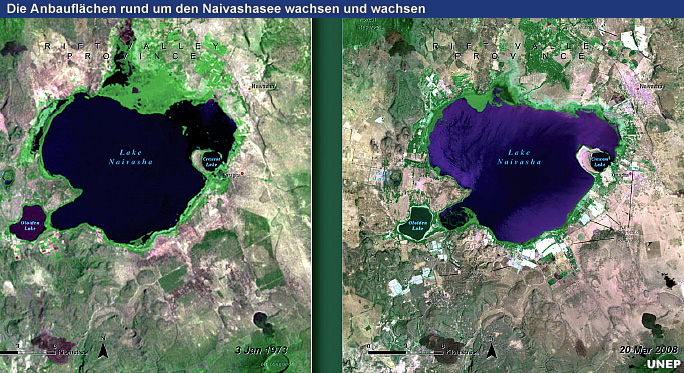

-

Lakes across the country are under intensified pressure, with Lake Naivasha

struggling to cope with the expansion of settlements and flower farms in

the towns of Naivasha and Karagita; Lake Turkana losing water through a

combination of decreased rainfall, increased upstream diversion and increased

evaporation due to higher temperatures.

-

Prosopis - a terrestrial shrub - has blocked pathways, altered river courses,

taken over farmlands, and suppressed other fodder species in the areas

around Lake Baringo since the 1980s.

-

Some estimates suggest that about half of the mangroves on Kenya's coast

have been lost over the past 50 years due to the overexploitation of wood

products and conversion to salt-panning, agriculture and other uses.

Towards

achieving the Millennium Development Goals and Vision 2030

According

to the data presented in the Atlas, Kenya has made some important strides

towards achieving some of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) - with

notable headway in the fight against poverty, the provision of universal

education and the fight against HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases.

Yet

challenges remain for Kenya on the road to achieving environmental sustainability,

notably limited government capacity for environmental management and insufficient

institutional and legal frameworks for enforcement and coordination.

The

Atlas notes that deforestation, land degradation and water pollution are

some of the challenges Kenya needs to address to achieve MDG7, 'Ensure

Environmental Sustainability'.

One

key finding of the Atlas is that achieving environmental sustainability

is fundamental to achieving all the MDGs. Environmental resources and conditions

have a significant impact on many aspects of poverty and development.

"One

of the most powerful ways to help achieve the first MDG - eradicate extreme

poverty and hunger - is to ensure that environmental quality and quantity

is maintained in the long term," the authors say.

For

instance, poor people often depend on natural resources and ecosystems

for income; time spent collecting water and fuelwood by children can reduce

the time at school; and environment-related diseases such as diarrhoea,

acute respiratory infection, leukemia and childhood cancer are primary

causes of child mortality.

"Vision

2030, with its ambitious development blueprint, is a key opportunity for

the Kenyan Government to address environmental challenges as a key element

underpinning the country's sustainability and development," concludes the

Atlas.

Kenya: Atlas of Our Changing Environment features numerous satellite images taken

around Kenya, along with 65 maps, 26 graphs and 229 ground photographs

illustrating the environmental issues faced by the country.

The

Atlas provides compelling visual evidence of the changes taking place in

30 locations across the country's critical ecosystems due to pressures

from human activities.

The

before-and-after display of satellite images spanning three decades highlights

forest loss, wetland drainage, shrinking lakes and coastal degradation,

as well as examples of good management and successful environmental strategies.

The

Atlas analyzes the linkages between the country's major socio-economic

activities and its key natural resources -illustrating, for example, the

link between agricultural productivity and forests, which regulate the

micro-climates that make farming possible.

The

Kenya Atlas follows on from UNEP's Africa: Atlas of Our Changing Environment,

published in June 2008, which gave an overview of environmental change

across the continent.

All

the materials in the Atlas are non-copyrighted and available for free use.

Individual

satellite images, maps, graphs and photographs, can be downloaded from

http://na.unep.net

The

Atlas can also be purchased at www.earthprint.com

The

digital version of the Atlas will also be released on Google Earth and

other websites.

|

| Source:

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2009 |

|

Kenya- Atlas of Our Changing Environment

|

|

nach

oben

|

Video

|

|

nach

oben

|

Kenia - Umwelt im Wandel

|

|

nach

oben

| Weitere Informationen |

|

| RAOnline: Weitere Informationen über Länder |

|

Links

|

|

|

|

Externe

Links |

|

|

Atlas

of Our Changing Environment

|

|

|

|