| Bhutan's

glaciers and glacial lakes |

|

Bhutan Glaciers - Glacial Lakes |

|

|

Bhutan Glaciers - Glacial Lakes |

|

|

|

|

Decline of World's Galciers expected to have Global Impacts over this Century |

The

great majority of the world's glaciers appear to be declining at rates

equal to or greater than long-established trends, according to early results

from a joint NASA and United States Geological Survey (USGS) project designed to provide a global assessment of glaciers. At the same

time, a small minority of glaciers are advancing.

|

Towns

and Cities Affected By Melting Glaciers

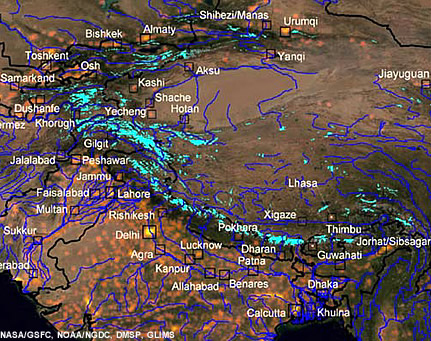

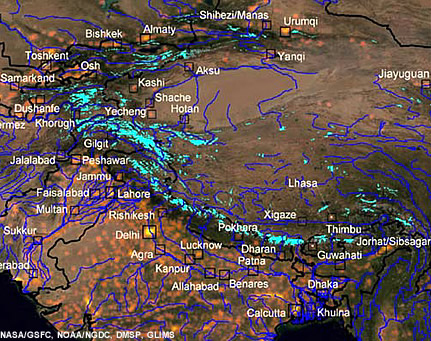

This

is a "Blue Marble" image from NASA, "Earth at night" is superimposed on

this (NASA/GSFC), Using the lights as an indication of population density.

The squares on the map highlight a representative number of cities within

the regions of glacier-fed areas. All of these areas derive some benefit

from melting glaciers. The implication is that if the glaciers melt away

completely, or substantially, these areas would be affected.

|

|

External

links |

|

|

Jeff

Kargel, a USGS scientist who will discuss glacier changes and their potential

political and economic impacts at the American Geophysical Union (AGU)

Spring Meeting in Washington, suggests that accelerating climate change

over the next century will directly impact the rate that glaciers retreat.

The

research is part of an international effort by glaciologists, coordinated

by the USGS, which uses NASA satellite imagery to map and assess glaciers

throughout the world during the middle to latter part of the melt season

when

permanent ice is exposed.

Current

glacier satellite images are being compared with topographical maps and

other records of glaciers from the 20th century. The project, called the Global

Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS), includes more than 100 collaborators

in 23 countries.

"Glaciers

in most areas of the world are known to be receding," said Kargel, who

is also the international coordinator for GLIMS. "But glaciers in the Himalaya

are wasting at alarming and accelerating rates, as indicated by comparisons

of satellite and historic data, and as shown by the widespread, rapid growth

of lakes on the glacier surfaces."

|

Glacial

Lakes From Melting and Receding Glaciers

This

composite image from the ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and

Reflection Radiometer) instrument aboard NASA's Terra satellite shows how

the Gangotri Glacier (India) terminus has retracted since 1780. Glacial

lakes have been rapidly forming on the surfaces of debris-covered glaciers

worldwide during the last few decades.

IMAGE

COURTESY: Jeffrey Kargel, USGS / NASA JPL / AGU

|

|

External

links |

NASA

ASTER

|

|

While

ice reflects the sun's rays, lake water absorbs and transmits heat more

efficiently to the underlying ice, kicking off a feedback that creates

further melting.

According

to a 2001 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,

scientists estimate that surface temperatures could rise by 1.4°C to

5.8°C by the end of the century. The researchers have found a strong

correlation between increasing temperatures and glacier retreat.

Glacier

changes in the next 100 years could significantly affect agriculture, water

supplies, hydroelectric power, transportation, mining, coastlines, and

ecological habitats. Melting ice may cause both serious problems and, for

the short term in some regions, helpful increases in water availability,

but all these impacts will change with time, Kargel said.

For

example, the Gangotri glacier between Kashmir and Nepal is retreating

at an accelerated rate that cannot be accounted for by lingering effects

from warming after the little ice age over 200 years ago. The Gangotri

glacier-and many others-feed the Ganges River Basin, upon which hundreds

of millions of people, including those in New Delhi and Calcutta, depend

for fresh water.

|

The

Gangotri Glacier, India: Last 200 Years

This

composite image from the ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and

Reflection Radiometer) instrument aboard NASA's Terra satellite shows how

the Gangotri Glacier (India) terminus has retracted since 1780. Contour

lines are approximate.

(Image

by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory; based on data provided by the ASTER

Science Team; glacier retreat boundaries courtesy the Land Processes Distributed

Active Archive Center)

|

|

Kargel

finds that over one percent of water in the Ganges and Indus Basins (South

Asia) is currently due to runoff from wasting of permanent ice from glaciers.

This contribution is expected to increase as melting rates accelerate,

though ultimately the added runoff is predicted to disappear as glaciers

decline many decades from now. Such changes are important since water use

in these basins is already approaching capacity as populations continue

to grow. In drier parts of Asia, like in arid Western China, wasting glaciers

currently account for over ten percent of fresh water supplies.

But

the research finds positive aspects to glacier changes as well.

"It's

not all doom and gloom," Kargel said. "Glaciers are wastelands, but as

they recede the land underneath may become available for use."

The

net loss or benefit of receding glaciers has not been calculated, but Kargel

suspects the overall impacts will be negative.

GLIMS

is designed to monitor the world's glaciers primarily using data from the ASTER

(Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and reflection Radiometer) instrument

aboard the NASA's Earth Observing System (EOS) Terra spacecraft,

launched in December 1999.

May

29, 2002

AGU

Press

|

More

Information

|

|

|

|

External

Links |

|